The museum is run by and associated with JAARS, ILS, and the Wycliffe Bible Institute. Essentially, the organization wants to be able to provide Christian Bibles to all peoples, and to do so, they sometimes have to help create alphabets and writing systems for languages that have heretofore been purely oral.

The museum appears to have been created to help educate the public about that last aspect of their work. Aside from a few instances where the museum leans biblical-literalist, the exhibits are fantastic and do a wonderful job of explaining how various cultures and individuals through the ages have invented or adapted ways of putting language into a written system. I had the impression that some of the staff’s opinions were much more literalist, but the exhibits were fabulous.

The museum starts out with a short film, and then a staff member introduces an interesting steel sculpture of the tower of babel, representing how multiple languages formed on earth. This is the only exhibit where the display took the Bible completely literally; the remaining exhibits were based on language research and language history.

For instance, the lovely tree of written language evolution, shown here in a postcard I purchased from their little gift-nook (sorry the quality isn’t high level. Wish I’d taken a picture myself. Basically, the top row is modern writing systems, and the branches show what was influenced by what other system or older form of the same system):

Once past that tree, the museum is divided into alcoves that each address a particular language or alphabet, and how their writing system came into existence and how it functions. There were also interactive portions, allowing you to answer questions, decode alphabets, or make sounds.

I was particularly fascinated by two exhibits, which I got permission to photograph:

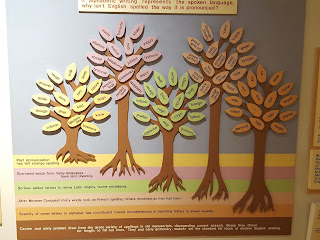

This chart is a FABULOUS explanation of various things that affect the crazy English spelling! Each tree matches the color of the paragraph below, which explains the cause of that particular type of spelling change or effect on modern spelling, and the leaves give example words.

I also was fascinated by this one, explaining that Korean orthography is actually based on the physiology of sound production. I have not researched this myself, so I am dependent on the museum’s research on this – but if this is true, this is awesome.

To return to my mention of Biblical influences, I would like to mention that each language exhibit has a Bible there, simply as an example of the orthography of that particular language. Given the purpose of the organization as a whole, I find this a completely reasonable example to have on hand.

The exhibit on Hebrew (the original form, not the modern form), posits that Moses himself came up with the alphabet when writing down the 10 commandments. Whether or not that is true, the concept that the ancient Hebrew alphabet came into existence in about that same era is still worth paying attention to.

Later exhibits focus more on the JAARS/SIL/Wycliffe work: since they are often working with languages that still have no written form. In these exhibits, there are examples of the linguistic work they do, which is fascinating to see! The linguists involved in this project learn the languages, try, at least in most cases, to find a writing system that will make sense with that language, and then also work on establishing and supporting literacy.

In all, this was a truly fascinating museum. It is small, but there is no entrance fee, and they do not accompany you on your tour, so you have as much time as you need and want to read all of the information – or to skip past it if you prefer!